Neo-Impressionism

Art movement

Neo-Impressionism is an initially French movement of the late 19th century that later spread all over Europe. It reacted against the empirical realism of Impressionism by relying on systematic calculation and scientific theory to achieve predetermined visual effects. By the mid-1880s, feeling that Impressionism's emphasis on the play of light was too narrow, a new generation of artists, including Georges Seurat, Paul Gauguin, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, and Vincent van Gogh, who would later be referred to more generally as Post-Impressionists, began developing new approaches to the line, color, and form. In 1879 after leaving the École des Beaux-Arts where he'd studied for a year, Seurat said he wanted to find his own new way of painting. He particularly valued color intensity and took extensive notes on the use of color by the painter Eugène Delacroix. He began studying color theory and the science of optics and embarked on a path that would lead him to develop a new style he called Chromoluminarism.

The discoveries of "optical blending" and "simultaneous contrast" that Seurat read about became the theoretical foundation of Chromoluminarism, which came to be known as Neo-Impressionism. While working at the Gobelins dye factory in Paris, French chemist Michel-Eugène Chevreul had to answer customer complaints about the quality of the yarn's color. While trying to address the problem, he discovered the principle of "simultaneous contrast," or the effect of the color of an adjacent yarn on the perception of another yarn's color. Subsequently, Chevreul wrote The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colors (1839). Later, American physicist Ogden Rood discussed in his Modern Chromatics (1879) how the viewer's eye "blends" or "mixes" adjacent colors, and Swiss aesthetician David Sutter established rules for the relationship between painting and science in his Phenomena of Vision (1880). To achieve the most brilliant colors and a shimmering effect, Neo-Impressionism relied upon applying dots or brushstrokes of complementary colors to the canvas. Rather than mixing pigments on a palette, Neo-Impressionist painters relied on the viewer's eye to "blend" the colors that appeared on the canvas.

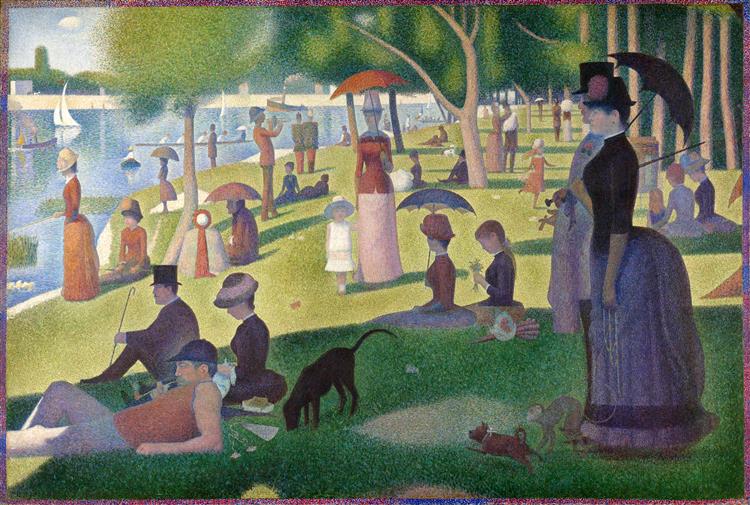

Though some of these theories are now considered only quasi-scientific, at the time they seemed cutting edge. Seurat felt he had discovered the science of painting, one that required discipline and precise application and that could achieve an intensity of color. He applied his color theory and a new technique that he called balayé, criss-crossing strokes to apply matte colors, in his Bathers at Asnières (1884), a monumental work that depicts a number of workmen bathing in the river on a hot summer day. Subsequently Seurat began work on A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-1886) by undertaking extensive preliminary studies and sketches. Depicting the bourgeoisie in the park along the river, the work used the Pointillist style Seurat developed - tiny dots of complementary colors placed next to each other. In 1890 Seurat published Esthetique, his foundational work on Neo-Impressionism's scientific color theory. Other Neo-Impressionists were to continue exploring this scientific basis; for instance, around 1887 Albert Dubois-Pillet developed the idea of passage, where the separate pigment of each of the primary light colors created a passage between different hues.

In 1884 the artist Paul Signac met Seurat and became an ardent advocate of both his color theory and his systematic working method. Though Seurat was the rigorous and reserved theoretician of the movement, Signac was its extroverted leader and advocate. The two men had a close working association, and it was Signac who came up with the name "Pointillism." In 1885, Seurat submitted Bathers at Asnières to the Salon, the official exhibition of the Academy of Beaux-Arts, but the committee rejected it. Not only were they perplexed by the painting's formal composition, monumental scale, and experimental technique, but Seurat's depiction of lower class workman during relaxation rankled the staid bourgeoisie and academicians. Subsequently, Seurat and Signac, along with Albert Dubois-Pillet and Odilon Redon, co-founded the Salon des Indépendants in response to the rejection. As a result, Camille Pissarro met Seurat and Signac in 1885 and both he and his son, the artist Lucien Pissarro, along with Henri-Edmond Cross, and Charles Angrand, became the first group of Neo-Impressionists.

1886 was a turning point in the art world, as the eighth and final Impressionist exhibit also marked the advent of Neo-Impressionism with the showing of Seurat's newly completed painting, A Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte. The only artist to have participated in all eight Impressionist exhibits, Pissarro invited Seurat to show in the exhibition. A Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte was also shown at the Salon of the Société des Artistes Indépendants where it drew even more attention, including that of the art critic, Félix Fénéon, who coined the term "Neo-Impressionism," and became an ardent advocate for the movement in the years that followed. Other French artists, such as Maximilien Luce, Leo Gausson, and Louis Hayet, also joined the movement.

While Seurat's particular politics are not entirely clear, from the beginning Neo-Impressionism was strongly connected to the anarchist movement, which had a strong foothold in France and in the artistic community. Before becoming an art critic for La Revue Blanche, Félix Fénéon was already famous for his anarchist sympathies. Arrested along with twenty-nine others, solely for their anarchist views, and charged with conspiracy in the assassination of Sadi Carnot, the French President, all thirty were found not guilty. As a result of the trial, Fénéon had a formidable reputation for independent thinking and defiance of social convention, and, as a critic, linked Neo-Impressionism with advocacy for anarchism. In the 1880s Signac became a committed anarchist, financially supporting the movement, and, along with Henri-Edmond Cross, Maximilien Luce, and Camille Pissarro, writing for the anarchist newspaper, Les Temps Nouveaux (The New Times.) He read Élisée Reclus and Peter Kropotkin, both radical geographers, along with Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, all of whom argued for a utopian society based on small groups and free association. These anarchists gave further impetus to Signac's view that Neo-Impressionist work was connected to a harmony derived from human freedom in a natural environment, which informed much of their subject matter. Furthermore, the artists' pursuit of scientific inquiry complemented their anarchist views in freeing them from the impositions of imposed tastes of the bourgeoisie.

Seurat died at a young age in 1891, and Signac became the putative leader of the group. The publication of Signac's manifesto From Eugene Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism, where he introduced the term Divisionism, led to a revival of the movement in 1898, making it an international movement, yet again allied with anarchist sympathies. The manifesto, along with his works like Saint-Tropez, the Storm (1895) drew a new generation of artists, including Henri Matisse. Signac became president of the Société des Artistes Indépendents in 1908 and held the position, advocating for Neo-Impressionism, until 1934, the year before his death.

Signac and Cross also created stylistic changes in Neo-Impressionism that had a great impact on other artists. Signac began using luxuriant color, as can be seen in his Capo di Noli (1898) with its pink mountains, and, rather than painting in dots, used small brushstrokes that allowed for dynamic flexibility. In his landscape, The Golden Isles (1891-1892), Cross used round brushstrokes in varying sizes to create a sense of perspective as the tiniest dots approached the horizon. Also showing the influence of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints in its high horizon, the work is notable for its near-abstract quality. But it was the mosaic-effect of his works like his La Plage de Saint-Clair (1896)that most influenced his contemporaries. To create this effect, Cross used short, wide brushstrokes that resembled small blocks and left small areas of the canvas unpainted. The emphasis was on keeping contrasting colors separate rather than having them blend. Cross felt as he said, "far more interested in creating harmonies of pure color, than in harmonizing the colors of a particular landscape or natural scene."

By the 1890s Neo-Impressionism had become an international movement, adopted by many European artists. The movement remained remarkably consistent in its reliance on color theory and its use of small dots or small brushstrokes. As a result, its development is best organized by regional interpretations. In France, Neo-Impressionism attracted a great many artists of successive generations, though each of them adapted the style to his individual preoccupations. A few Impressionists, including Camille Pissarro and Charles Angrand, took up the movement. Pissarro, using the Pointillist technique, retained his work's focus on rural life and peasant labor. Angrand used a more muted palette to depict shadow and tone, as shown in his 1887 Couple in the Street. Maximilien Luce depicted more contemporary scenes, often passionately portrayed with intense contrasts of light. In the 1890s with the revival of the movement, a new generation of artists was influenced by Neo-Impressionism. Cross's mosaic-like work influenced Signac, as well as younger artists like Henri Matisse, Henri Manguin, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay, and André Derain. These artists also individually adapted the style, as can be seen in Metzinger and Delaunay's use of small brushstrokes to resemble small cubes of color, and in Matisse's evolution toward an ever more intense color palette.

The Belgian Impressionist Théo Van Rysselberghe was stunned by Seurat's A Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte when he saw it in Paris in 1886. Along with a group of other artists, including Georges Lemmen, Xavier Mellery, Willy Schloback, Henry Clemens van de Velde, Alfred William Finch, and Anna Boch, he introduced the style to the Belgian art world where it had a significant influence. From his travels to Morocco, he created a number of pointillist landscapes, but it was his Portrait of Alice Sethe (1888) that became his signature work. Due to his influence portraiture became a significant aspect of Belgian Neo-Impressionism. Alfred William Finch, a founding member of the Les Vingt (Les XX), a Brussels group that tried to free Belgian art from narrow nationalistic traditions by focusing on French contemporary models, saw the work of Seurat and Signac at Les Vingt show in 1886 and also became a leading proponent. Depicting an empty sky above a surging sea, his Breaking Waves at Heyst (1891) has a strong emphasis on pattern and design, which has a flattening and decorative effect. The emphasis on the pattern of colors is also apparent in the work of Henry Clemens van de Velde.

From 1882-1890, Dutch artist Jan Toorop studied in Brussels where he encountered the work of Seurat and Signac. He developed an individualized style that synthesized Divisionism with other artistic influences that he had encountered and was recognized as an important innovator in Holland. His Neo-Impressionist painting, Broek in Waterland (1889), depicting a couple in a boat along a canal at sunset, has a strong element of design and pattern. He joined the Hague Art Circle and helped organize an exhibition, that presented the works of Seurat, Signac, Pissarro, Rysselberghe, Van de Velde, and others. The exhibition received a great deal of favorable attention and was visited by Van de Velde who created a number of significant relationships with Dutch artists. As a result, the young artists Johan Joseph Aarts, Petrus Bremmer, and Jan Vijibrief became Neo-Impressionists. Bremmer was to have a significant influence as a teacher and a writer, urging the use of a bright clear palette.

However, the most important innovative Dutch artists to take up Pointillism and Divisionism early in their careers were Vincent van Gogh and Piet Mondrian. Van Gogh met Signac in 1887 in Paris and adopted elements of the style into his highly individualized expression. Of a later generation of artists, Mondrian adopted the style, and wrote in 1909, "I believe that in our period it is definitely necessary that, as far as possible, the paint is applied in pure colors set next to each other in a pointillist or diffuse manner. This is stated strongly, and yet it relates to the idea which is the basis of meaningful expression in form." Both artists moved beyond Neo-Impressionism to explore and develop other artistic means.

The artist and art critic Vittore Grubicy de Dragon introduced Neo-Impressionism to Italian artists in the late 1880s (they mostly identify themselves as Divisionists). He spent 1882-1885 in the Netherlands, where he met and was influenced by the artist Anton Mauve, a cousin-in-law of Vincent van Gogh and an advocate for the movement. At the First Triennale in Milan in 1891, two Divisionist works received the most attention. Giovanni Segantini, who had an international reputation, exhibited The Two Mothers (1889) to great acclaim, while Gaetano Previati's Motherhood (1890-1891) was violently attacked. Previati had intensely studied Divisionism and had written the only scholarly work on the technique at the time. While having advanced knowledge of the perception of color, he also felt that by using intense color to vividly engage the eye an emotional and spiritual resonance would be felt. Motherhood is now viewed as the debut work of Italian Neo-Impressionism, and a turning point for Italian modern art with its engagement with Symbolism and its influence on Italian Art Nouveau and Expressionism.

Divisionism was to be centered primarily in Northern Italy, and while the work often focused on landscape, it reflected Segantini's statement that art has "nothing to do with the imitation of the real, because creation is possible only through the drive of the spirit and the human soul." Giuseppe Pelizza da Volpedo's The Mirror of Life (1895-1898), depicting a flock of sheep in a landscape, was described by the artist Cesare Viazzi as conveying "the living sense of perfect calms ought in the gentle abandonment of Nature's predestined events." Many of the works were Symbolist, or at least allegorical, and there was also an intent to often reply to social conditions. Pelizza's most famous work was The Fourth Estate (1901). Originally titled The Path of Workers and depicting a strike, the work became a rallying symbol for the Italian socialist movement.

The 1890s in Germany and Austria marked an era of Secessions, art movements that broke away from the conservatism of official academies and emphasized modern art. The Munich Secession of 1892, Vienna Secession of 1897, and Berlin Secession of 1898 had no manifesto and exhibited the work of all the contemporary movements, and Neo-Impressionism was featured prominently. Artists like Berliner Curt Hermann adopted the style, though combining it with the Naturalism of en plein air painting.

However, the style had the greatest influence on a younger generation of artists. Following the translation of Signac's From Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism into German in 1903 and the Neo-Impressionist show of 1904, the Expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner painted Divisionist works like Park Lake in Dresden (1906). Other young artists adopted the style, as seen in Karl Schmidt-Rottluf's Gartenstrasse early in the morning (1906) and Erick Heckel's The Elbe at Dresden (1905), and inched it toward Expressionism as seen in Heckel's furious brush strokes to depict the churning water. For these artists, Neo-Impressionism was an international style that broke the dominance of Impressionist art, allowing the artists to focus on the properties and potential effects of color alone.

Even after Seurat’s death in 1891, Neo-Impressionism had a wide influence, both upon individual artists and the development of art movements including Art Nouveau, Fauvism, Cubism, Die Brücke, Orphism, Italian Futurism, and the movement toward abstraction. As art historian Claire Maignon wrote, "Neo-Impressionism showed a capacity for abstraction - in the sense of 'to subtract from' - that was a constituent element of its modernity. From the world, it extracted formal qualities, universal archetypes, color sensations and lines that would be the departure points for many modernist experiments." While many artists took up the technique and then moved on to other styles, Signac, one of the original Neo-Impressionists, continued to paint in the style until his death in 1935.

Neo-Impressionist techniques and theories have had a continuing influence on more contemporary artists. American Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein created works like Drowning Girl (1963) by using stencil dot patterns that not only recall the printing process of newspapers and magazine but also the dots of color in Neo-Impressionist paintings. Chuck Close and John Roy both incorporated Pointillism with Photorealism. Using a grid pattern, Close used a variety of 'points,' from pixels to cells, in creating his work. The Dutch artist, Ger van Elk, has created a number of what he calls flatscreens, moving images based on the paintings of the works of Seurat, Signac and Cross, Snow over Seurat and Seurat's La Grève de Bas-Butin à Honfleur, both shown simultaneously in 2004 in Amsterdam.

And finally, Seurat's Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte can be found often in popular culture. Steven Sondheim's 1984 Broadway musical, Sunday Afternoon in the Park with George, which won the Pulitzer Prize and two Tony awards, is based on the painting. The work has shown up in movies, like Barbarella (1968) and, significantly, in Ferris Bueller's Day Off (1986). Cartoons like Looney Tunes, Sponge Bob, and The Simpsons have all parodied it, as have children's books and shows like Babar the Elephant and Sesame Street. Countless magazine covers have recreated the image.

See also Neo-Impressionism (style), Pointilism (style), Divisionism (style)

Sources:

www.theartstory.org

www.britannica.com

Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neo-Impressionism