Outsider art

Style

The term Outsider art was coined by art critic Roger Cardinal in 1972 as an English synonym for Art Brut, a label created by French artist Jean Dubuffet to describe art created outside the boundaries of official culture; Dubuffet focused particularly on art by those on the outside of the established art scene, such as psychiatric hospital patients and children.

While Dubuffet's term is quite specific, the English term "Outsider art" is often applied more broadly, to include certain self-taught or naïve art makers who were never institutionalized. Until the 1980s, two terms were used synonymously, but later, however, the term "Outsider art" had expanded to encompass a much greater range of vernacular and “marginal” arts. This broadening was particularly important in the United States, where a rich vein of art that reflected racial, religious, and localized histories rather than psychiatric or spiritualist ones had grown independently from Art brut. Known successively—and at times concurrently—as “popular painting,” “modern primitive art,” “self-taught art,” and “contemporary folk art,” works from the American scene were first made visible and analyzed in the 1930s by Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) curator and WPA Federal Art Project art director Holger Cahill, collector Sidney Janis, and others.

Typically, those labeled as Outsider artists have little or no contact with the mainstream art world ("insider artists") or art institutions. In many cases, their work is discovered only after their deaths. Often, Outsider art illustrates extreme mental states, unconventional ideas, or elaborate fantasy worlds. The “classic” figures of Outsider art were socially or culturally marginal figures. They were usually undereducated; they almost invariably embraced unconventional views of the world, sometimes alien to the prevailing dominant culture; and many had been diagnosed as mentally ill. These people nevertheless produced—out of adversity and with no eye on fame or fortune—substantial high-quality artistic oeuvres.

Outsider artists usually experience some sort of revelatory moment, akin to a religious calling when they become "artists". They typically have no formal training within an art institution and exhibit in their work a sense of heightened connectivity within the intricate system of universal balance. Without having necessarily experienced tragedy, these artists hold within an acute awareness of the forces of darkness as well as those of light. The Outsider artist deals incessantly with a war in mind (which is often mistakenly labeled as mental illness), always navigating emotional conflict in order to create outwards paths to find inner peace. The closest more conventional movement comparable is Surrealism, as the premise of the latter is also based on the power of the human unconscious. The Outsider Artist however does not feel the same impetus to share and disseminate ideas, often they only ask, humbly and without expectation, to be left quiet and uninterrupted to make art.

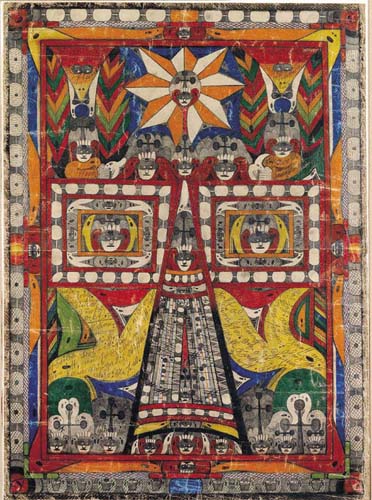

There is no one style or aesthetic that defines Outsider painting and drawing, although Outsider artists do share a tendency to certain themes and motifs. For example, there is an interest in portraits, fish, birds, repetition, binding, linking, and entirely filling a given space. They employ techniques of pattern, and obsessive repetitive design features as is an attempt to create simple and satisfying order when they themselves are typically touched by an awareness of chaos. The repetitive mark-making also reveals a profound understanding of the passage of time, of the continuum of a cycle, and the eternal linkage between past, present, and future. The tendency towards the repetitive is highlighted not only in endless similar marks made in drawings, but also through the acts of sewing, knotting, and binding.

Many artists, like Gaston Duf, Adolf Wolfli, Heinrich Anton Müller, and Jeroen Pomp, create fantastical images derived from their vivid imaginations (including cities, people, animals, all often encased within geometrical shapes). However, there are other Outsider artists, like Stephen Wiltshire, Gregory Blackstock, and James Castle, whose images offer extremely realistic reproductions of existing things or places. What sets these latter artists apart is that they do not follow any pre-existing artistic style or movement, such as Cubism or Expressionism (although coincidentally, similarities sometimes exist). They also, despite making more "realistic" pictures at first glance, like the more classic outsiders (Wolfli) do fill designated space, and do attempt to create order by using art. As Colin Rhodes, Professor of Art, writes, "One of the most striking features of Outsider Art is its general tendency to present the world in transcendent or metaphysical terms [...] Almost invariably artists develop a structured cosmology that underpins the 'reality' of their worlds, although the viewer does not always have access to the language of their articulation. Indeed, individuals often deliberately engage in obscurantism or develop complicated iconographies in order to protect themselves and their ideas from perceived threats."

As with painting and drawing, Outsider sculpture can take many forms and styles. However, as many of these artists create(d) their works inside the confines of institutions (such as mental asylums and prisons), the materials to which they had access tended to be more limited. Thus Outsider sculptures often demonstrate resourcefulness on the part of the artist, who uses whatever found objects and materials they can get their hands on, including animal teeth, bones, and pelts found in asylum farms, and other sorts of refuse such as string, cord, and wire. Outside of institutions and without enforced restriction, outsider artists making sculpture tend to continue the theme of using waste and disregarded objects. The Cornish artist, David Kemp, uses entirely found materials, often harmful debris washed up by the sea to make his sculptures. As such the final pieces are at once a slap in the face to greedy and ignorant consumer culture and a testament to outsider artists who defy fashions and trends to always prioritize meaning.

Visionary environments include large-scale environments or architectural projects created by Outsider artists, such as Simon Rodia's Watts Towers, SP Dinsmoor's Garden of Eden, Ferdinand Cheval's Palais Idéal, and Nek Chand's Rock Garden. As editor of Raw Vision magazine, John Maizels, explains, Visionary environments tend to be "unusual structures, full of strangeness and individuality" which "are often the results of years of committed toil" and "represent one of the most extraordinary forms of human creativity." These environments tend to be created from a vast array of found materials, such as stones and garbage / found objects, and they often contain a mixture of styles, drawing from various forms of architecture. A significant proportion of these projects are found in France and the United States.

See also Outsider art/Art brut (art movement), Art Brut (style)

Sources:

www.britannica.com

www.visual-arts-cork.com

www.theartstory.org