Socialist Realism

Art movement

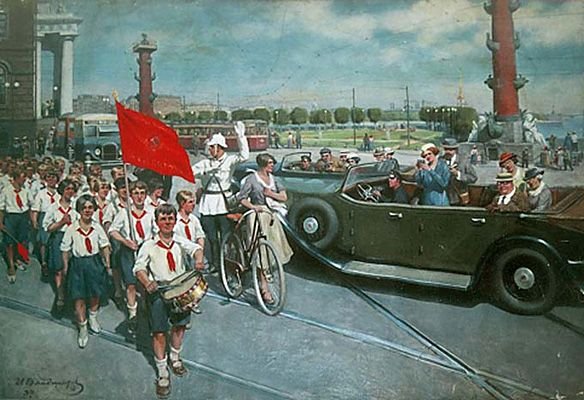

Socialist realism is a style of realistic art that was developed in the Soviet Union and became a dominant style in that country as well as in other socialist countries. Socialist realism is characterized by the glorified depiction of communist values, such as the emancipation of the proletariat, by means of realistic imagery. Although related, it should not be confused with social realism, a type of art that realistically depicts subjects of social concern.

Socialist realism was the predominant form of approved art in the Soviet Union from its development in the early 1920s to its eventual fall from popularity in the late 1960s. While other countries have employed a prescribed canon of art, socialist realism in Soviet Union persisted longer and was more restricted than elsewhere in Europe.

Socialist realism was developed by many thousands of artists, across a diverse society, over several decades. Early examples of realism in Russian art include the work of the Peredvizhnikis and Ilya Yefimovich Repin. While these works do not have the same political connotation, they exhibit the techniques exercised by their successors. After the Bolsheviks took control of Russia on October 25, 1917, there was a marked shift in artistic styles. There had been a short period of artistic exploration in the time between the fall of the Tsar and the rise of the Bolsheviks. In 1917, Russian artists began to return to more traditional forms of art and painting.

Shortly after the Bolsheviks took control, Anatoly Lunacharsky was appointed as head of Narkompros, the People's Commissariat for Enlightenment. This put Lunacharsky in the position of deciding the direction of art in the newly created Soviet state. Lunacharsky created a system of aesthetics based on the human body that would become the main component of socialist realism for decades to come. He believed that "the sight of a healthy body, intelligent face or friendly smile was essentially life-enhancing." He concluded that art had a direct effect on the human organism and under the right circumstances that effect could be positive. By depicting "the perfect person" (New Soviet man), Lunacharsky believed art could educate citizens on how to be the perfect Soviets.

There were two main groups debating the fate of Soviet art: futurists and traditionalists. Russian Futurists, many of whom had been creating abstract or leftist art before the Bolsheviks, believed communism required a complete rupture from the past and, therefore, so did Soviet art. Traditionalists believed in the importance of realistic representations of everyday life. Under Lenin's rule and the New Economic Policy, there was a certain amount of private commercial enterprise, allowing both the futurists and the traditionalists to produce their art for individuals with capital. By 1928, the Soviet government had enough strength and authority to end private enterprises, thus ending support for fringe groups such as the futurists. At this point, although the term "socialist realism" was not being used, its defining characteristics became the norm.

The first time the term "socialist realism" was officially used was in 1932. The term was settled upon in meetings that included politicians of the highest level, including Stalin himself. Maxim Gorky, a proponent of literary socialist realism, published a famous article titled "Socialist Realism" in 1933 and by 1934 the term's etymology was traced back to Stalin. During the Congress of 1934, four guidelines were laid out for socialist realism. The work must be:

This is a part of the Wikipedia article used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA). The full text of the article is here →

Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Socialist_realism